Jorge Adarne's dog Lily

Courtesy of Jorge Adarme

The Pets of Whitehead Institute

This story is part of our ongoing series, Beyond the Lab Bench. Click here to see all stories in this collection.

Considering that researchers at Whitehead Institute devote their working hours to probing the mysteries of the biological world, it’s no surprise that many scientists and staff are also animal lovers.

The Institute has, in fact, served to connect pets needing a home to a new family. Christine Hickey, assistant to Founding Member Robert Weinberg, has a golden-doodle (a golden retriever-poodle mix) named Finley.

Sabatini lab manager Edie Valeri says that she met Finley shortly after starting her job here and “fell in love.” Hickey helped Valeri find Finley’s three-month-old half-brother, who Edie named Chancellor—Chance for short.

Chancellor (“Chance”)

Photos: Courtesy of Edie Valeri

Soon, though, Chance got into some trouble. He ate a poisonous toad that burned his esophagus. Valeri rushed Chance to Angell Animal Medical Center, where veterinarians performed emergency surgery to bypass his esophagus and insert a feeding tube.

Valeri had to feed Chance through the tube and keep it clean. “This was a 24-hour watch,” she says. “I was only about six months into the position here and was really nervous about asking David [Sabatini] about keeping my dog at work. However, David was super understanding and supportive.”

Chance began coming to work every day, typically hiding under Valeri’s desk. Many Sabatini lab members pitched in to help feed and walk him. Chance recovered and, 10 years later, is now 100 pounds and can’t fit under Valeri’s desk.

“He’s healthy, happy, and well-loved,” Valeri says. “Working at Whitehead helped me to find the love of my life.”

A number of people at the Institute have adopted pets from shelters. Cheeseman lab postdoc Ally Nguyen adopted a street dog from India through a rescue dog program in New Jersey. Administrative Lab Manager Jorge Adarme of the Page lab adopted Lily, a four-year-old Shih Tzu, from a shelter in Louisiana. He and his wife had been trying to adopt a puppy for eight months before getting a call about Lily from a friend of his wife’s.

Lily through the years

Photos: Courtesy of Jorge Adarme

“Lily is kind of spoiled,” Adarme says. “There are dog pajamas in my house. She did not like them.” Lily is very energetic and friendly, leading many to think she’s still a puppy.

After adopting Lily, Adarme found out that Shih Tzus are a very smart breed. “It took just a day to house train her,” he says. Lily is able to roll over, dance with her hind legs, shake, and high-five. But the strongest sign of her intelligence, Adarme explains, has been her ability to train every member of his family to do “whatever she wants and make sure that they know that she is second in command.”

Pets help people stay balanced—and sometimes they help out with work in unexpected ways. Sabatini lab postdoc Izabella Pena’s cat Mike has a science-communication-themed Twitter account, @MikeScienceCat. “Everybody in the lab knows him,” says Pena.

A Twitter post from Mike the Science Cat: "Grant approved! The first equipment for my kitty lab arrived today! I'm doing experiments with it now. #MikeScienceCat #experiments"

Other times, animals playfully undermine what their humans are trying to do. Institute Member Sebastian Lourido has a six-year-old Shiba Inu named Kafka, as a reference to Haruki Murakami’s novel Kafka on the Shore.

“Shibas are very stubborn, very independent, very lupine,” Lourido says. “She sometimes gets this glimmer in her eye, and you know it’s going to be difficult to retrieve her. And then I’m chasing her around the neighborhood. It then becomes a game to her, but I’m trying to get to work.” Lourido has a secret weapon, though: “Her weakness is cheese. I keep some string cheese with me when I’m walking her.”

Sebastian Lourido and Kafka

Photo: Courtesy of Sebastian Lourido

Lourido studies Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite that is transmitted from cats to humans. That hasn’t affected his decision not to have a cat, though, he just prefers dogs. But lab members Emily Shortt and Ben Waldman both have cats.

Shortt, the Lourido lab manager, adopted two cats from Michigan as barn kittens. “They moved with us to Massachusetts when they were three months old — just imagine driving kittens for 16 hours,” she says. “Miko, the striped cat, is mischievous and smart; he opens cabinets and tries to turn doorknobs. Lily is just in it for the snuggles, feline or human.”

Lily (left in top photo) and Miko

Photos: Courtesy of Emily Shortt

Some at Whitehead Institute have less common creatures. Nicholas Polizzi, administrative lab manager for the Cheeseman and Reddien labs, began caring for some aquatic pets that once belonged to a Cheeseman lab member who passed them on to Polizzi after she began medical school. Among them is a suckermouth catfish named Dyson and an axolotl named Montgomery. Axolotls (Ambystoma mexicanum) are a species of amphibian that lives its whole life in an aquatic, gill-breathing form, without going through metamorphosis. Montgomery is lively and curious about visitors, making his way over to their side of the tank to inspect them more closely.

Montgomery the axolotl

Montgomery once had an axolotl tank mate named Geoffrey. Unfortunately, the pair had to be separated when Montgomery bit off one of Geoffrey legs. Fortunately, Geoffrey demonstrated the regenerative capability of the species by growing the limb back, but after the incident Montgomery and Geoffrey no longer shared a tank.

Technical Assistant Olivier Paugois, who manages the Sive lab’s zebrafish population of 2000-3000 individuals, also keeps his own fish. He enjoys trying to recreate the conditions in the fish’s native habitat, known as a biotope setup in the aquarium world. Paugois began doing this after he learned to free-dive in Brittany, France, when he was 15 or 16 years old. He would capture fish and try to incorporate shellfish and sediment from the ecosystem where he found the fish.

Olivier Paugois and his fish

The tank at his desk hosts a small school of dwarf loaches (Ambastaia sidthimunki). Endangered in the wild but frequently bred for aquariums, the species is native to rivers in Thailand and Myanmar. “They like a gentle flow of water, not too strong,” says Paugois. His careful attention to their needs has allowed them to live to about 5-6 years old. “That’s pretty decent for a fish of this small size,” he says. At home, Paugouis keeps a tank of several cichlid species native to Lake Malawi in East Africa—a place with a famously high number of native fish species. “Fish diversity is really amazing once you dig below the surface,” he says.

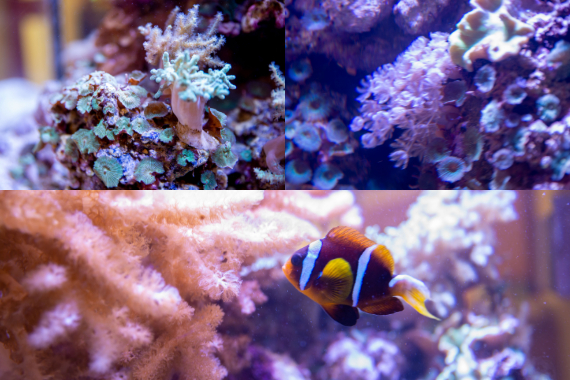

Sabatini and his lab keep a saltwater aquarium that showcases coral diversity as well as several tropical fish. Administrative lab manager Danica Rili, who feeds the fish, says that the pulsing xenia coral, which constantly opens and closes to feed, is one of her favorites. The tank also has Devil’s hand, tree coral, toadstool coral, and green star polyps. The corals make a good home for the resident clownfish, coral beauty, and royal gramma.

The Sabatini lab aquarium

While not everyone at the Institute has a pet, Lourido sees having an animal as typical of one type of path to working in biology. “Some people come to biology through medicine and an interest in disease,” he says. “Other people are interested in solving complicated problems and are pursuing intellectual puzzles. And some are naturalists that like to explore the natural world—and those are the ones that tend to have pets.”

Animal companions help keep busy people tied to the world around them—and sometimes they just help their person step away from work and think about other things for a moment.

Mike the Science Cat reacts to a grant application in progress.

Contact

Communications and Public Affairs

Phone: 617-452-4630

Email: newsroom@wi.mit.edu